Pnina Werbner

is Professor Emerita in Anthropology at Keele University and author of The Making of an African Working Class: Politics, Law and Cultural Protest in the Manual Workers' Union of Botswana (Pluto Press 2014). In this post Pnina considers how

Western ‘bad news’ perspectives on Africa disguises the strength of civil

society and trade unions in protecting democracy and the public interest.

About the same time Botswana 24

October 2014 , there were runoff presidential elections in Brazil Tunisia Botswana Botswana BCP ),

which had shortsightedly refused to join the main opposition alliance, thus

splitting the vote in many constituencies. But the writing was clearly on the

wall for the Botswana establishment: young people and city dwellers were fed up

with the status quo, which had led to allegations of cronyism, corruption,

secret surveillance and ‘tendrepreneurship’(corruption in awarding public

contracts), emanating in the popular view from presidential autocracy.

|

| Cartoon of President Khama tied to a tree |

Despite his alleged autocracy, however, the

President, Lieutenant General Ian Khama, was a democratic, publicly committed

to giving up his office lawfully after two terms, as spelled out by the Constitution.

This would mean, in effect, passing the presidency onto his Vice-President

mid-term, as had happened when Khama himself became President. African

presidents are known for their repeated attempts to extend their constitutional

rights to office, clinging on to power come what may. In the case of Khama, the

prevailing rumour was that he intended to appoint his younger brother to the

vice-presidency, despite the latter's political inexperience and lack of

popularity. In the local press, headlines proclaimed Khama's ambition to create

a 'dynasty'. This led to a series of cliffhangers which tested Botswana

|

| Unionist leaders in front of the High Court and Court of Appeal Building |

Before Parliament was dissolved it

passed a ruling allowing for the election of the Vice-President, the Speaker of

the House and the Deputy Speaker in parliament by secret ballot. After the

elections, the President, through the office of the Attorney General,

challenged this ruling in the High Court and later the Court of Appeal. The

accepted view was that an open ballot would allow him to intimidate members of

his own party, despite the widespread feeling, reported in the press, that

elected parliamentary members of the BDP strongly objected to the nomination of

the President's brother.

|

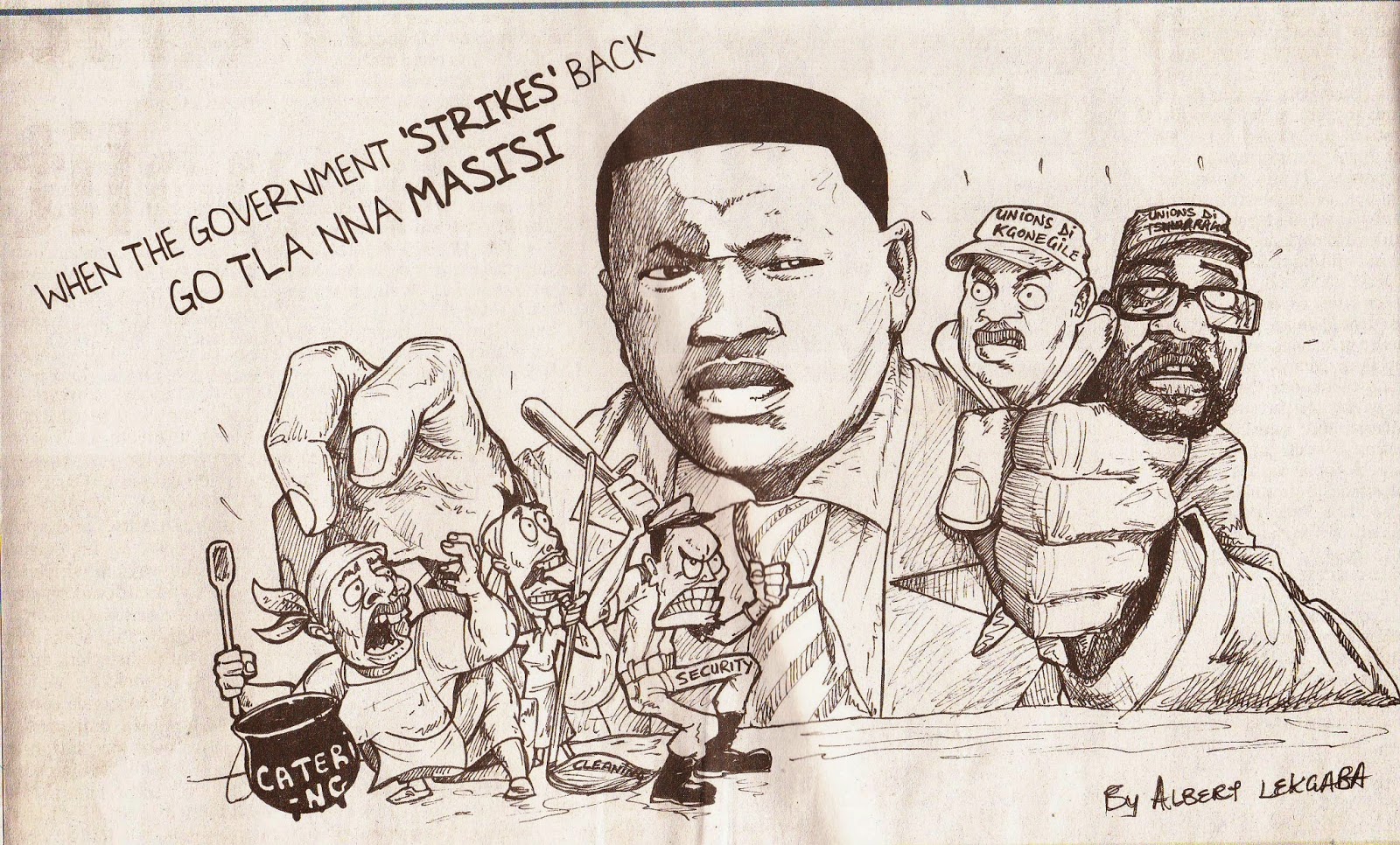

| Cartoon of Masisi, now Vice-President, oppressing workers |

As always in Botswana Botswana Botswana

|

| Duma Boko, leader of the Opposition, speaking to public sector union strikers |

As in Tunisia Brazil Botswana

The global media's myopia with regard to

Botswana Africa are growing in confidence and strength. It would

seem to be the duty of the media to support these nascent African democracies,

and at the very least report on their struggles, rather than engaging merely in

tired Afropessimistic reportage.